Form Follows Fiction: Trolling Bari Ziperstein’s “Propaganda Pots”

Written by Michael Slenske

“All art is propaganda, and ever must be, despite the wailing of the purists.”

— W. E. B. Du Bois

“A lie told often enough becomes the truth.”

— Vladimir Ilyich Lenin

When Bari Ziperstein was invited, five years ago, to do a residency at the Wende Museum, a Los Angeles institution devoted to the art, history and cultural artifacts of Europe and the former Soviet Union during the Cold War, she was at best hoping to find some vacation advertisements for the old brutalist hotels scattered throughout the Eastern Bloc. To Ziperstein, who has been making semi-surrealist sculptures and brutalist vessels for the past 15 years, advertising was a gateway drug into the pop history of these concrete architectural marvels.

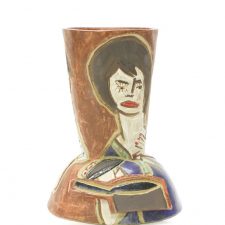

But when the Chicago-born, Los Angeles-based artist arrived at the Wende, her practice—long centered around the merger of the body and the built environment, be it in the form of brutalist “lady finger” vessels or porcelain nipples grafted onto the bodies of slip cast matrons (some sprouting architectural support beams from their shoulders)—took an unexpected turn. In the Culver City-based museum’s archives she happened upon a Russian propaganda poster from the 1980s featuring two women sitting on a park bench. The working woman to the right was a study in polish, from her tightly coiffed brunette bob and tasteful gold jewelry to her smart green blouse and stylish blue-lensed eyeglasses; the “working woman” to the left, however, was a lightning bolt of red hair sutured into a mini skirted armature punctuated by stiletto heels and a cigarette she wielded like a dagger. The Russian caption above them read: “Women for sale are cheap though are paid plenty, so why is she looking down when she fell so low?”

The taunting juxtapositions of these misogynistic sub-narratives and neo-constructivist forms—in this poster and countless other Soviet-era examples warning against the houses (and hangovers) of ill repute—offered a compelling and confounding mise en scene for Ziperstein to explore in clay.

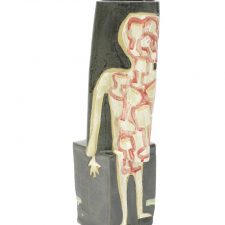

“For me it’s about forensically figuring out how history plays a part of these images and why,” says the artist. As such, shortly after discovering this bounty of Russian propaganda she went about translating the two-dimensional image of the propagandized prostitute into a classical vessel. Her body snake around the surfaces of the stoneware cylinder—the positive and negative images of the source material bleeding into one another—and her head became an intersecting planar top offering four views of her psyche. By fracturing the three-dimensional figure into four 2-D planes this multidimensional form simultaneously begins to evoke Picasso-esque perspective shifts and the flatness of the original.

For Ziperstein, the ability to “slow down the read” of the poster propaganda allowed her not only to bridge the narrative from paper to clay, creating multiple entry points into the work(s), but in doing so, as a contemporary American female artist, she reclaimed power over images manufactured by the iron-fisted, male-dominated Soviet state.

“She’s a ‘nasty woman’ and a working woman but I would have to say that we are all both of these,” argues Ziperstein, who went on to make vessels referring to the bespectacled office worker from that first poster and translate a series of other ads (some propping up the communist work ethic by celebrating Russian factory laborers; others hilariously warning against the perils of alcoholism) into a body of work she simply refers to as “Propaganda Pots”. A seminal vessel from that early period merges two of these warning in a picture of a seemingly libidinous woman breastfeeding while drinking a glass of wine. The imagery is at once playful, even humorous, but also appalling. Yet through the artist’s clay abstraction the viewer can see this woman’s plight from many angles—figuratively, and then quite literally, via Ziperstein’s tooled planes.

“I think feminism tries to break things down where something has to be this way or that—bad mom or good mom; madonna or whore,” explains Ziperstein. “But I think feminism is messy and it’s the job of feminism to not wrap itself up in a bow.”

Instead of being the targets of misogynist propaganda, Ziperstein’s figures—whose bodies, clothing, and accessories are further embellished via mixes of matte and gilded glazes (and underglazes) with pops of raw stoneware as hard nods to the flesh; figurative outlines carved with a needle tool for added depth; and deftly painted costumes and cosmetics balanced against textile patterns to emphasize new graphical contrasts and narrative twists—become multivalent emblems of towering feminine power. (Each pot averages 22 inches in height.) The residual effect turns these former victims of female-on-female animosity, and the leering objectification of men, into business owners who, like Ziperstein herself, wield the body and feminine mystique to create something transformative for their own aims.

Though Ziperstein had been building this new body of work—and a series of ceramic armature installations evoking Soviet textiles and Cold War-era trade show displays—since 2013, she never found the proper venue to showcase it until the Art, Design, & Architecture Museum at UC Santa Barbara offered her a solo show, ultimately titled Fair Trade, last January. During the time Ziperstein created the work and prepared for the show the country was focused on women’s issues as they related to Hillary Clinton’s historic presidential campaign and the stark contrast it offered against that of Donald J. Trump’s, especially after the infamous Access Hollywood tape—and the Republican candidate’s “Grab ‘em by the pussy” comments on it—leaked to the media.

In the wake of Trump’s surprise victory, however, these pots took on new dimensions. While the inauguration-trolling Women’s March certainly amplified the feminist codes in Ziperstein’s work, once all 17 US intelligence agencies confirmed in early January that Russia indeed meddled in the 2016 election, the nation’s focus shifted away from feminist identity politics—at least for a time—to the possibilities of Russian collusion, a “second Cold War”, and a new Red Scare under Putin.

In real time art began imitating life and the “Propaganda Pots” adopted new meanings and interpretations, which was poetic justice to Ziperstein, whose ancestors are Jews—many of them rabbis—that emigrated from the former Soviet Union. For a moment, Ziperstein could have her Russian tea cake and eat it, too. Now the “Propaganda Pots” simultaneously examined the warnings against “nasty women” in Cold War Russia—when Putin was working with the KGB—and investigated Trump’s warnings against that “Nasty Woman” (aka Hillary Clinton) from the stage of a presidential debate directly after he implored Russia to hack the Secretary of State’s emails.

And just as truth (or at least truthiness) has become stranger than fiction in the age of Trump, Ziperstein’s figurative pots have taken on increasingly strange forms—from classical perfume bottles and Greek vessels to more intuitive arrangements, all hand-built with hump molds, leather hard slabs and extruded clay parts formed around shipping tubes and over plastic bowls sourced from the 99-cent store. Her most recent works are even beginning to embrace the “awful familiarity” of propaganda from the Cuban revolution to the Haight-Ashbury hippies, which presaged the end of the American empire via identity politics, the selling off of our National Parks, even tax breaks for the 1%.

While ceramics are often thought of more as craft vehicle than political cudgel, to quote Toni Morrison, “All good art is political!” The beauty of Ziperstein’s pots is that they invite viewers into the political arena by being, first and foremost, lusciously aesthetic. Where Betty Woodman once bent the language of Persian vases, majolica and Baroque architecture into that of mural painting, geometric abstraction, and ancient tapestries to stake out a feminist perch in the male-dominated ceramics field of the 1960s, Ziperstein is bending agitprop into the language of brutalism, cubism, and dark humor for her own aims. Thanks to pioneers like Woodman, Beatrice Wood, and Lucie Rie—and the serendipity of living in these interesting times—her clay can speak directly to a #notsurprised movement upending the old art world patriarchy while a newly liberated American public propels the leaders of #metoo (aka “The Silence Breakers”) onto the cover of Time magazine as the 2017 Persons of the Year.

Spurred on by this third (or fourth?) wave feminism, and a Russia investigation that is continually flipping new witnesses in the Trump campaign, transition, and administration—just as Nixonian level propaganda is being pushed out of the White House on a daily, sometimes hourly, basis—Ziperstein is constantly broadening the scope of her practice. She may be touching the pulse of the zeitgeist right now, but there is no kiln in the world that can keep up with Twitter feed of @realDonaldTrump. Ceramics is not the medium of rapid response, it’s a slow build, leather hard, hope it doesn’t crack under the fire art form.

Which leads us to Ziperstein’s “Prop Art” exhibition at Bethel University. In addition to a series of pots inspired by Russian propaganda, the show will feature a collection of new works drawn from the recently released tome See Red Women’s Workshop: Feminist Posters 1974-1990 as well as the seminal posters of the Women’s Liberation Movement, which fought for parity with the patriarchy in the US during the late 1960s and 1970s. One particular pot of note references a 1970 poster featuring the Statue of Liberty brandishing a clenched fist. Rendered upside down in matte black this isolated version of Lady Liberty is confounding and hypnotic as she appears to strip away any notions of chauvinistic nationalism as a menacing graphic trapped inside this scallop-edged Brutalist tower. For Ziperstein, such examples are spaces for drawing comparisons between the Russian bootlegger and the bra-burning Vietnam protester, each of them women working to better their place in society be it in Moscow or Manhattan.

“The system doesn’t want these women to be empowered,” adds Ziperstein. For her, the political power of art—especially in this moment—is as tactile, fragile, and immediate as one of her ceramic pots. “It’s in the translation into clay, isolated from these posters in a gallery or apartment setting, that’s where things can shift.”